Visual Tone Poems: Landscape Art Inspired by Classical Music

The color of music.

Painting has color. So does classical music. All my adult life I have intensely enjoyed the many connections of tonal quality between the two art forms. Read on, and see if you feel the same.

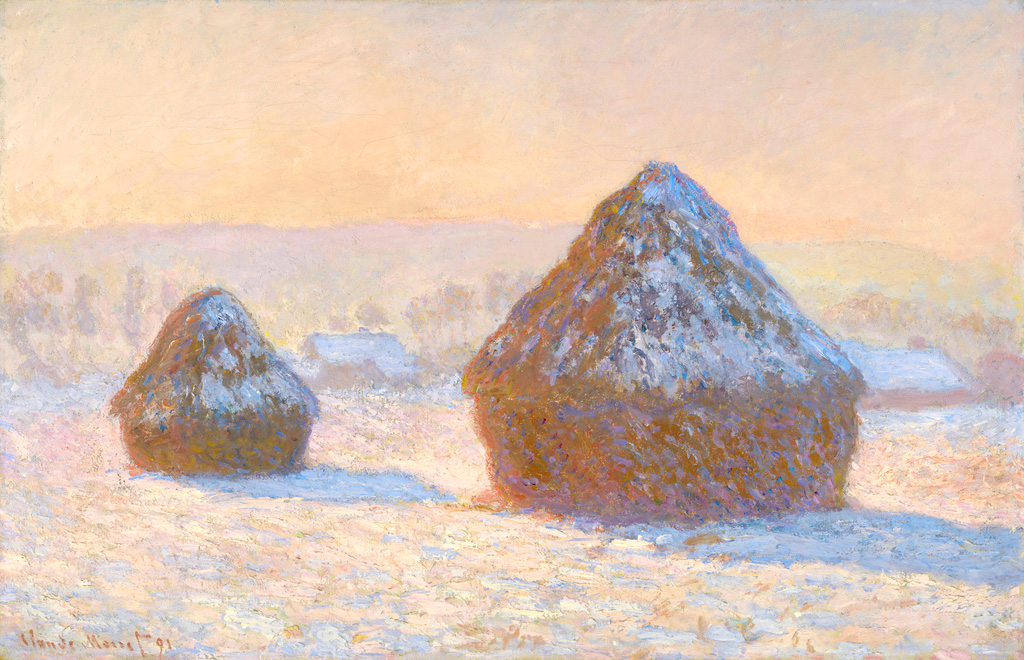

Both arts radiate tonal color, and certain styles of expression within each art form accentuate color as the dominant characteristic of the work. Some abstract paintings for example, are built around color itself. It’s literally what they are all about. Form is present just enough to articulate large swaths of rich hues, without being deliberately descriptive of anything in the real world. Color rules.

Classical music can be every bit as rich, but the colorful tones tend to conjure up imagery, oddly enough. Tonal color in orchestral music can be just as expressive as different hues and shades in painting. They are painterly, but in a musical sense. And probably the most painterly of all musical forms is the tone poem.

The tone poem: evoking the feeling of landscape

According to Wikipedia, a tone poem in classical music usually refers to a piece of orchestral music, most of the time in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, or landscape.

As a landscape artist, the “tone” reference is of particular interest to me. It opens up the audio space to such an extent that it invokes real 3 dimensional space in my imagination and senses. And I love to carry that feeling through all of my artwork.

Often, if a piece of music has certain characteristics, the space it invokes is the feeling of a landscape, whether intimate or grandiose. Landscape forms share so many similarities of structure with classical music, particularly symphonic pieces: peaks, valleys, abrupt cliffs and gentle slopes all feature in the topology of music.

Contours and textures

Listening to certain pieces of music I get a real sense not only of contour, but of texture and atmosphere and even altitude as well.

What about you? Do certain pieces of music lift you right out of your chair and carry you off into nature? What pieces transport you to the hills, to the mountains, to the sea? Feel free to comment on my Facebook page.

Here are a few personal selections of music that inspire the feeling of landscape within me.

Music that inspires the sense of landscape: a few personal picks:

Beethoven Symphony #7

First up is the Beethoven symphony that gave me my epiphany of awareness around the age of 25 while on a road trip through the Adirondack mountains around Lake Placid, New York: Symphony #7. The first movement sostenuto, with its expansive chords, immediately evokes for me glimpses of the grand scale and lush green textures of towering mountains, seen through gaps in the trees while driving through the valley roads. And the second movement, the allegretto, never fails to lift me up, higher and higher, through patches of fragrant mist, up the climb to the peak of Mount Washington. A breathtaking experience, magically conjured up through music.

Beethoven Symphony #6, the Pastoral

Probably the most famous, the rolling hills of Beethoven’s 6th symphony, the “pastoral” is one piece that almost anyone who hears it acknowledges as a landscape for the ears. Yes, it is actually titled as such: Beethoven’s full title was “Pastoral Symphony, or Recollections of Country Life.” So sure, we’re predisposed to consider it as the musical impression of a landscape, but Beethoven the landscape artist created such a masterpiece of natural musical forms, rhythms and contours that the connection totally rings true.

Peer Gynt Suite, Edvard Grieg

Another famous piece that invokes the feel of a romantic vision of nature is “Morning Mood”, first movement of the Peer Gynt Suite #1 by Edvard Grieg. The title still somewhat hints at an outdoor scene but even if it were untitled, there’s no doubt that it would conjure up a beautiful landscape in one’s imagination.

My video piece above explores the connections between the landscape forms in one of my works entitled “Prairie Symphony #1” and Grieg’s Morning Mood. My intent was to use simply a virtual camera, and one piece of art… pan and zoom, and fade, and nothing else. As an animator I have plenty of concepts for more complex explorations. Stay tuned, subscribe to my personal announcement email list for developments.

Please give it a like on Facebook and share it if it resonates with you.

A piece of music certainly doesn’t need to be deliberately titled to be evocative of the spirit of landscape, though….

Gabriel Faure, Sicilienne

Conjuring some of the more intimate impressions of landscape are the Sicilienne by Gabriel Faurē. That one always opens up a glimpse into a quiet woodland valley full of dark green foliage and cool, filtered light on the forest floor.

Apres Midi d’un Faun, Claude Debussy

Another is the Afternoon of a Faun by Claude Debussy. It’s more of a shifting view that seems to expand and contract with the ebb and flow of shimmering intensity within the music. A broader view opens to sunlight, then meanders through 3 dimensional layers of colorful shade, then turns to explore another half hidden intrigue of the forest. It’s easily one of the most evocative pieces in all of music. A true force of nature. As colorful as a painting.

Mendelssohn’s Scotland: The Hebrides and the Scottish Symphony

At the other extreme, several symphonic pieces by Mendelssohn open up grand romantic vistas of misty Scottish highlands and the craggy coastlines of England, with the Scottish Symphony and the Hebrides Overture.

The Hebrides is a great example of exactly how classical music can conjure up pictures and atmospheric scenes out of lines of musical notes.

What seems to create a landscape vision are in particular a series of rising scales and passages that seem to layer and build, one on top of the other, like an eagle soaring up the heights of a coastal mountain, from surf to rocks to slope to cliffs to peak to clouds. Darkly dramatic and deeply spatial.

La Mer, Debussy: perhaps the Ultimate soundscape?

Impressionism is perhaps the pinnacle of the musical expression of place. Another piece from Debussy, “La Mer” is arguably the supreme masterpiece of landscape art in all of classical music. Ethereal, atmospheric harmonies, so vivid you can almost smell the seacoast, rhythmic passages that suggest powerful surf and spray upon rocks, and a grand scale, whirling ebb and flow genuinely capture the imagination – the visual imagination – and hold it spellbound by the majesty of the sea.

Soundscapes like these radiate tonal color that truly paint pictures in the mind.

In my own art my aim is to traverse that heady connection between the spatial qualities of classical music and landscape art. Look through my work and see if you can sense it.

Do you have a favorite piece of music that always conjures up the feeling of landscape? Please share it with me in the comments section below. I hope to influence a few orchestras and musicians to feature this theme in their program selections. Your comments will help move this along. Thanks!

Let me know what your own favorite pieces of “musical landscape” are on Twitter and Facebook!